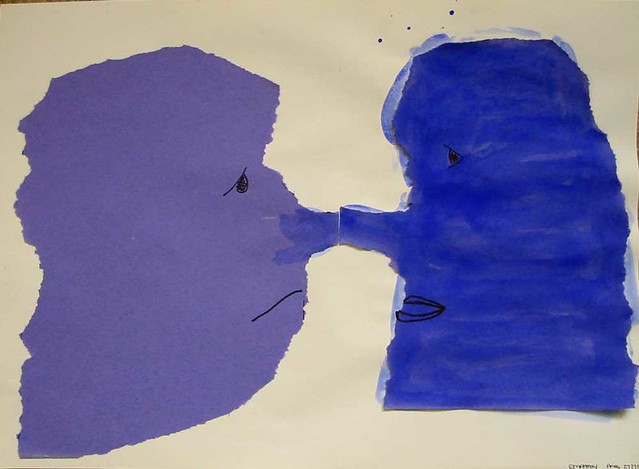

Empathy by The Shopping Sherpa

Another Sunday morning, another stimulating conversation about medical education on Twitter.

It started with a tweet from Dr. Jonathon Tomlinson “To say you cannot learn insight and empathy is like saying you cannot learn science or a new language. Possibly true, but very sad.”

So can we teach empathy? What do we mean by empathy? A good review of the complexities was published earlier this year by some researchers from the University of East Anglia. They suggest that we might be better to step away from the concept of empathy and instead just focus on etiquette. It's a provocative read.

I wonder if teaching empathy isn't like teaching clinical reasoning. We need to first think of empathy as a disposition before concentrating on the skills. The following quote comes from a just-published study on how physicians think about clinical reasoning in students, is it an ability or a disposition? : "The ability-disposition distinction highlights the difference between teaching knowledge and skills, referred to as teaching-as-transmission, versus teaching attitudes, modifying personality and changing behaviour, referred to as teaching-as-enculturation."

So how can we transmit what we think is important to others about empathy? A few years ago, I blogged about a communication skills session that I was teaching. I was aware of how this session on "breaking bad news" had to some become formulaic. But an interesting discussion did occur and we all questioned our thoughts and approaches to the topic.

Just as Krupat et. al suggest that in order to develop clinical reasoning we need to focus on "encouraging self-awareness and mindfulness, modelling open discussion and inquiry, accepting doubt and uncertainty", I'd suggest that the same is true of developing empathy.

What we do not want is for students to leave thinking that empathy is just a set of behaviours. As this doctor tweeted: ""Empathy by rote" is a ridiculous concept. It's like teaching somebody to be "happy". Faked empathy is insulting."

Another doctor replied that to his mind one of the worst examples of this was: “ to score on 'empathy' student said 'sorry it has to be me to tell you this'”. The doctor was shocked as he saw this as the student putting “professional discomfort before patient distress”. It’s this kind of situation that we exactly need to tease out when talking to students about empathy and communication.

In a comment on a blog post by a doctor about breaking bad news, a patient writes of her feeling when she was told she had a serious condition. She explains how the doctor “As he spoke, he began to sip little bits of air in between his lips. This suggested to me he was feeling emotions as well. It made him more human and incredibly compassionate. I loved him for that.”

For some patients showing that we are human and have emotions to will be right. For others it might be seen selfish. They might want us to have ‘professional distance’, to just get on with the job. How with someone that we don’t know well can we figure out how to be? Do we have to accept that sometimes we will just get it wrong and that etiquette is the best we can aim for?

I don’t expect to reach the answers to those questions through this blog. But they are the kind of issues we should discuss with students when we are in real-life situations, so that we can help them to start developing their sensitivity to communication and their inclination to becoming good communicators.

More tweets can be seen in the storify here.

Regina Holliday tells the powerful story of a doctor who seems to lack all empathy here.

Excellent post on empathy by oncologist, Robert Miller, here.

Previous posts on medical students' thoughts about teaching and learning about empathy:

A medical student's thoughts on empathy and #meded

A twitter conversation with UK medical students about empathy

More tweets can be seen in the storify here.

Regina Holliday tells the powerful story of a doctor who seems to lack all empathy here.

Excellent post on empathy by oncologist, Robert Miller, here.

Previous posts on medical students' thoughts about teaching and learning about empathy:

A medical student's thoughts on empathy and #meded

A twitter conversation with UK medical students about empathy

I would imaging may be tricky to teach empathy explicitly: would lead to a stage performance where trite phrases are repeated rather than a 'feeling-with'. Modelling behaviour seen in other clinicians may be the best way. Empathy, for psychiatrists, has an additional meaning that is worth bearing in mind: it is usually the word we use to translate the German 'Verstehen' - a term from hermeneutics and used by Schliermacher, Dilthey, and Jaspers. Here empathy is a tool one uses clinically to follow the narrative account a person gives of events, following their rationality. Jaspers suggested that in trying to understand primary delusions, empathy fails. But this meaning has little to do with co-experiencing emotional states but rather, understanding their internal reasoning

ReplyDeleteWell, I think we perhaps focus too much on 'demonstrating empathy', on showing the behaviours, rather than talking about empathy as something that we think or feel. Have you read the Samjdor paper?

ReplyDeleteI've just seen your comment "perhaps need to rationally relate to someone to get the emotional connection? and that needs time: otherwise become vets". Time seems to be a very important, maybe the most important factor. I#m sure (lack of) it is what leads doctors to behaving in ways that seem so unbelievably cold and harsh. Or perhaps I'm being generous. The most recent case I can think of is this story of Regina Holliday's experience: http://reginaholliday.blogspot.com/2011/05/little-miss-type-personality-reginas.html

Great post. I added a few thoughts of my own - http://post.ly/22rIQ

ReplyDeleteI agree that aspects of empathy are probably teachable, with an underlying inherent ability to see one's self in the other's shoes/situation. But not everyone is good at that part of it. It takes a certain skill, interest and dedication to empathize well. At least that's what I believe and see with my own eyes.

Thanks Paul. I thought I would post in your blog post on this:

ReplyDeleteEmpathy - Great topic.

In medical school there was a brief class or two on ethics and similar non-clinical aspects of medicine (although things may have changed since I was a student during 1992-1996). I believe that, to a large extent, the ability to empathize comes from within. But how we demonstrate empathy to our patients is the trick and I believe that such behavior can be taught, or at least honed.

Empathy is “Identification with and understanding of another's situation, feelings, and motives.” It is a challenge to be able to do so both mentally and physically, although such identification is made easier if you have experienced similar pain. Example: after suffering a cut that needed stitches, I learned that the local anesthetic, lidocaine, burns upon subcutaneous injection, but that lidocaine buffered with sodium bicarbonate does not. It is only one component of empathy – the ability to understand another's physical plight - but it is a useful one.

The other component - that of emotional empathy - is much more ingrained, in my opinion. There are people who "get it" and those who do not. Many people assume that all doctors and nurses should be great empathizers. But of course doctors and nurses are human and each human has different abilities, including the ability to empathize with another person.

It seems to me that each of us has the capability and capacity to empathize well, but some of us focus on honing those skills and others shy away from them. As an interventional radiologist, I often participate in the care of people when they are at their sickest. I have been the first person to discuss that a CT scan result has a high likelihood of cancer. I have had to tell people that the procedure they are about to undergo carries with it an uncommon, though definite, risk of death. Many doctors go through these and similar issues every day. I am by no means unique. Nor do I expect or suggest that I am the best in my role as empathizer.

But it is important that each of us, who takes on these roles, attempts to understand, commiserate and empathize with our patients to the best of our abilities. Eye contact, a smile, a word, a handshake are sometimes all that matters to a patient.

I have been visiting US simulation centers and watching videotapes of patients breaking bad news. In one of the recorded encounters the student started with "I'm sorry that I'm the one having to tell you." The body language and voice clearly signaled that the student was uncomfortable in the situation.

ReplyDeleteMy reflections:

Student's need guidance: hard to break news - makes people people uncomfortable. Some of these students with emotional communications difficulties can improve, others are not suited to be doctors and work with patients.

pjh - I wouldn't say that anyone is or is not suited to be a doctor merely because they are "good at" empathy or not. But one would hope that such individual has enough introspective ability to choose a pathway that might limit their need to use empathy.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comments.

ReplyDeletePaul, your take on empathy is in common with the way it is often talked about, as a set of behavioural skills. I think that this model is probably lacking. But at the same time trying to 'feel with' or to understand the thinking processes of another is a very big ask. Your recommendation that a smile, a handshake etc might be all that matters fits very well with the Smajdor review. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21292696

It is certainly the very bear minimum that we should expect.

@PJH Thanks for posting your thoughts as well. I guess I am a little less concerned about a student or a young doctor saying, "I am sorry that I'm the one having to tell you...". Why is a young doctor in this position? Maybe it genuinely would be better for the patient to have a more senior colleague inform about the bad news? Maybe the junior doctor is correct to feel sorry for the patient in this situation?

ReplyDeleteWhen we use a phrase like this to friends or family we are trying to demonstrate that we know this is bad for them. It's so bad that we don't want to be the one saying it.

Is the unease about a doctor using a phrase like this a reflection of a notion that we have that we should be able to never show our own emotions. In the example I give above the woman comments that it is expression of emotion, and hesitancy by the doctor which lets her know that he really does care.

Usually when doctors run into communication problems it is because they don't show emotion (as in sensitivity to the patient) that they have problems. Regina Holliday's husband's doctor doesn't seem to feel anything for her situation at all. Is it feeling too much that leads some doctors to block themselves off from the emotions of others and to come across as caring and unfeeling?

Just some thoughts. Thanks again.